by Anne Laurel Carter

illustrated by Akin Düzakin

In this memorable story, a young boy finds solace flying his kite from the rooftop after soldiers take his father and brother away.

Without his father and brother, the young boy’s life is turned upside down. He and his family have to stay inside, along with everyone else in town. At suppertime, he can’t stop looking at the two empty places at the table and his sister can’t stop crying. The boy looks out the window and is chilled to see a tank’s spotlight searching the park where he plays with his friends. He hears shouts and gunshots and catches sight of someone running in the street — if only they could fly away, he thinks.

Each day the curfew is lifted briefly, and the boy goes to the park to see his friends. One day, inspired by the wind in the trees, he has an idea. Back at home he makes a kite, and that night he flies it from his rooftop, imagining what it can see.

In this moving story from Anne Laurel Carter, with haunting illustrations by Akin Duzakin, a young boy finds strength through his creativity and imagination.

Editorial Reviews

From School Library Journal

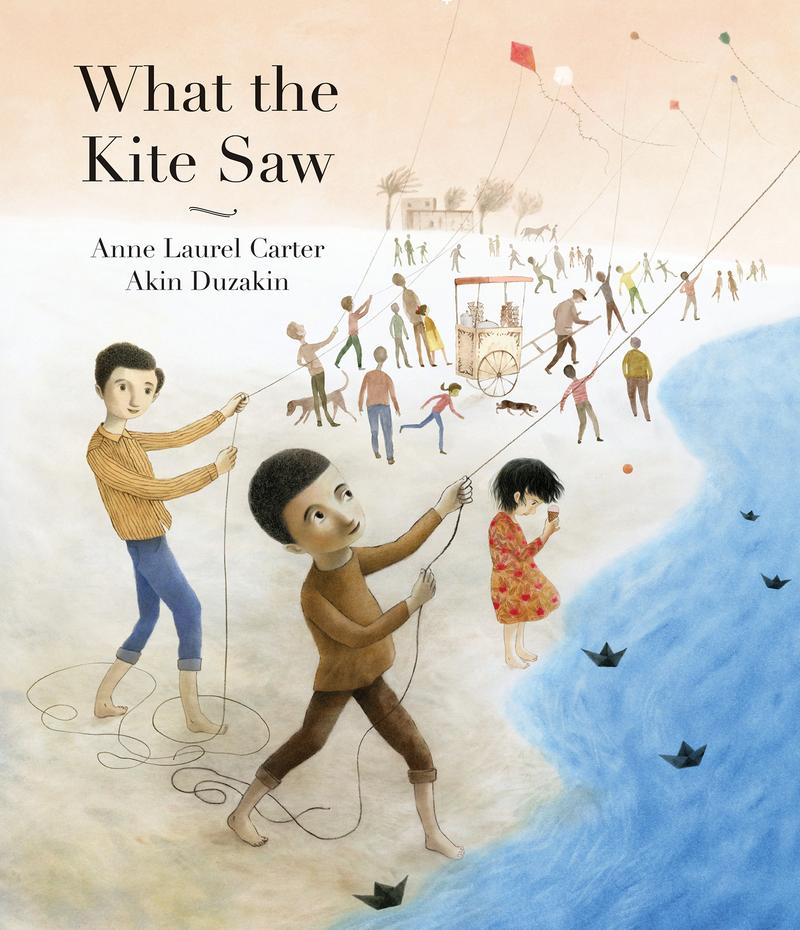

K-Gr 2—The world shifts on its axis the day soldiers occupy a young boy’s town. His father and brother are taken away, leaving his family reeling from the uncertainty left in their wake. When a curfew is imposed that restricts people to their homes for the greater part of each day, the boy does what he can to improve the moods of his mother and younger sister. One day, the boy has an idea that he shares with his friends as a way to bring hope to a frightening situation. He creates a kite, and then imagines the view of the world from the kite’s lofty height, including, on a distant spot, his brother and father waving at him. Though short-lived, the boy’s creation inspires more stories to light the darkness surrounding them. Soft, pastel illustrations create the visual atmosphere of this story, emphasizing browns and grays with a few chosen accents of brighter colors. The threat of war is unsettling at best, and feelings of fear and helplessness are evident on the people’s faces, primarily with light skin, although a few of the townspeople have darker complexions. As the story progresses, the buildings in the background begin to crumble, adding more to the narrative than the words alone provide. Simple text and vivid, emotion-filled imagery make this book well-suited to a wide range of readers. Adults will find echoes of World War II atrocities, although the author’s small note credits the inspiration for her story to Palestinian children. VERDICT This hopeful story is an important means of understanding and coping with the realities of war in one’s backyard.—Mary Lanni, formerly at Denver P.L.

From Kirkus

In a word, powerful.

The first-person account of a child living through military occupation.

Though an author’s note says the story was inspired by Palestinian children, neither text nor illustrations specify where or when it takes place. Instead, it recounts a young child’s experience when soldiers in tanks occupy their town, taking father and brother away, which leaves the child with mother and a younger sibling. (The narrator has pale skin and dark hair, as do other family members.) The illustrations employ a muted palette of somber grays and browns with limited, expressive color indicating at turns danger and hope. The town is under a strict curfew, with the ever looming threat of the occupying force, though the art keeps overt violence off the page. Powerful compositions make the menace clear, such as one that foregrounds uniformed soldiers holding assault rifles with an array of staring children in the background looking tiny by comparison. The titular kite emerges as a symbol of hope and freedom when the child leads friends in making kites to fly above their town. When soldiers shoot them down, the child cuts the string and imagines it sailing away. With that act, the child imagines seeing what the kite sees. An affecting final scene shows the winged child flying above a vision of two figures standing by the sea. They can be read as the lost father and brother or perhaps as their spirits, lending a poignant ambiguity to the story’s end. (This book was reviewed digitally with 10-by-17-inch double-page spreads viewed at 17.5% of actual size.)In a word, powerful. (Picture book. 5-8)